Locals who live off U.S. Highway 89 north of Yellowstone National Park say it’s not a matter of if you’ll hit an animal, but when.

U.S. Highway 89 is one of the main arteries into Yellowstone, following the Yellowstone River for 55 miles between Livingston and Gardiner through Montana’s Paradise Valley. The valley is home to a murderer’s row of North American wildlife, including bison, elk, pronghorn, grizzly and black bears, bighorn sheep, and wolves, and hundreds of thousands of people travel to Yellowstone’s North Entrance each year using Highway 89 to see these animals. In 2023 alone, 400,000 people visited the park through the North Entrance—that means lots and lots of cars on the road, and cars and animals typically don’t get along.

Montana has the second-highest wildlife-vehicle collision rate in the country, with 10% of car accidents in the state involving animals, but on Highway 89, it’s five times that. Between 2012 and 2023, there were 1,685 documented cases of animals killed by cars on that 55-mile stretch, and an estimated cost of $32 million in personal injury and property damage (if you add the estimated cost of wildlife loss, that number jumps to $72 million). The actual number of animals killed is almost certainly higher, and the death toll includes skunks, raptors, owls, deer, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, bison, elk, grizzly bears, black bears—even one unlucky mountain lion.

The price of passage—of both animals and humans—is mounting. And some people in Paradise Valley want to do something about it.

BY FISCHER GENAU

This mobile sign is one of the few preventative measures in place to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions on Highway 89. PHOTO BY FISCHER GENAU

Daniel Anderson grew up in the Tom Miner Basin, just over the hill from the valley’s Yankee Jim Canyon, and he’s driven Highway 89 more times than he can count. When he was in high school, he was driving the highway with his girlfriend in her parents’ minivan when they struck a white-tailed deer, which he called “a pretty horrible experience.” Anderson watched as each year, more and more animals were hit by cars there, and when he eventually went to grad school at the University of Montana, he started working on solutions.

At the time, the only preventative measures in place were a few signs along the roadway warning drivers of the presence of wildlife. In school, Anderson did a project on the potential for wildlife crossings in Paradise Valley, which would allow animals like elk and bears to pass over or under the highway to cross safely to the other side. After he turned it in, Anderson’s professor encouraged him to start a conversation about wildlife crossings outside of the university, so he called a handful of nonprofits and other organizations, including the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Park County Environmental Council, Center for Large Landscape Conservation, and the National Park Conservation Association, and brought them together in Bozeman for a meeting in December of 2019. At that meeting, Anderson shared his vision for a community-led collaborative that would keep the conversation about wildlife-vehicle collisions on Highway 89 alive long enough to build momentum and actually find solutions. Everyone who attended the meeting was on board, and Yellowstone Safe Passages was born.

At the time, the only preventative measures in place were a few signs along the roadway warning drivers of the presence of wildlife. In school, Anderson did a project on the potential for wildlife crossings in Paradise Valley, which would allow animals like elk and bears to pass over or under the highway to cross safely to the other side. After he turned it in, Anderson’s professor encouraged him to start a conversation about wildlife crossings outside of the university, so he called a handful of nonprofits and other organizations, including the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, Park County Environmental Council, Center for Large Landscape Conservation, and the National Park Conservation Association, and brought them together in Bozeman for a meeting in December of 2019. At that meeting, Anderson shared his vision for a community-led collaborative that would keep the conversation about wildlife-vehicle collisions on Highway 89 alive long enough to build momentum and actually find solutions. Everyone who attended the meeting was on board, and Yellowstone Safe Passages was born.

For the coalition’s first two years, it didn’t have a name or a leader—initially Anderson just wanted to “work independently as the dude from the valley,”—but the group kept growing, drawing more attention to wildlife-vehicle collisions on Highway 89 and working towards a solution.

Wildlife crossings are proven to be the most effective way to keep animals and people safe on roads like Highway 89, but they are still relatively new in the United States. They can take the shape of overpasses that arch above a road, underpasses that burrow beneath them, and even culverts and bridges that are designed or modified to offer animals safe passage. Crossings first gained popularity in European countries like France and Germany, before being adopted by Canada to great effect in Banff National Park in the 1980s and 90s. The first wildlife crossing built in the United States was an underpass designed for panthers in Florida’s Alligator Alley in 1988, and to date, there are nine wildlife overpasses in the country and about 700 underpasses.

Despite Montana having the second-highest rate of wildlife-vehicle collisions in the country, so far only one wildlife overpass has been completed there, on U.S. Highway 93 on the Flathead Indian Reservation (it was built at the request of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes in 2010, and they called the 197-foot wide vegetated bridge the “Animals’ Trail”). Other sites in the state have been identified as candidates for wildlife crossings, including the notoriously dangerous stretch of Highway 191 between Bozeman and Big Sky, but none have been constructed.

Yellowstone Safe Passages and Anderson have been working towards the construction of a wildlife overpass, perhaps several, on Highway 89 for years, and they’re getting closer and closer to realizing their goal.

Wildlife crossings are proven to be the most effective way to keep animals and people safe on roads like Highway 89, but they are still relatively new in the United States. They can take the shape of overpasses that arch above a road, underpasses that burrow beneath them, and even culverts and bridges that are designed or modified to offer animals safe passage. Crossings first gained popularity in European countries like France and Germany, before being adopted by Canada to great effect in Banff National Park in the 1980s and 90s. The first wildlife crossing built in the United States was an underpass designed for panthers in Florida’s Alligator Alley in 1988, and to date, there are nine wildlife overpasses in the country and about 700 underpasses.

Despite Montana having the second-highest rate of wildlife-vehicle collisions in the country, so far only one wildlife overpass has been completed there, on U.S. Highway 93 on the Flathead Indian Reservation (it was built at the request of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes in 2010, and they called the 197-foot wide vegetated bridge the “Animals’ Trail”). Other sites in the state have been identified as candidates for wildlife crossings, including the notoriously dangerous stretch of Highway 191 between Bozeman and Big Sky, but none have been constructed.

Yellowstone Safe Passages and Anderson have been working towards the construction of a wildlife overpass, perhaps several, on Highway 89 for years, and they’re getting closer and closer to realizing their goal.

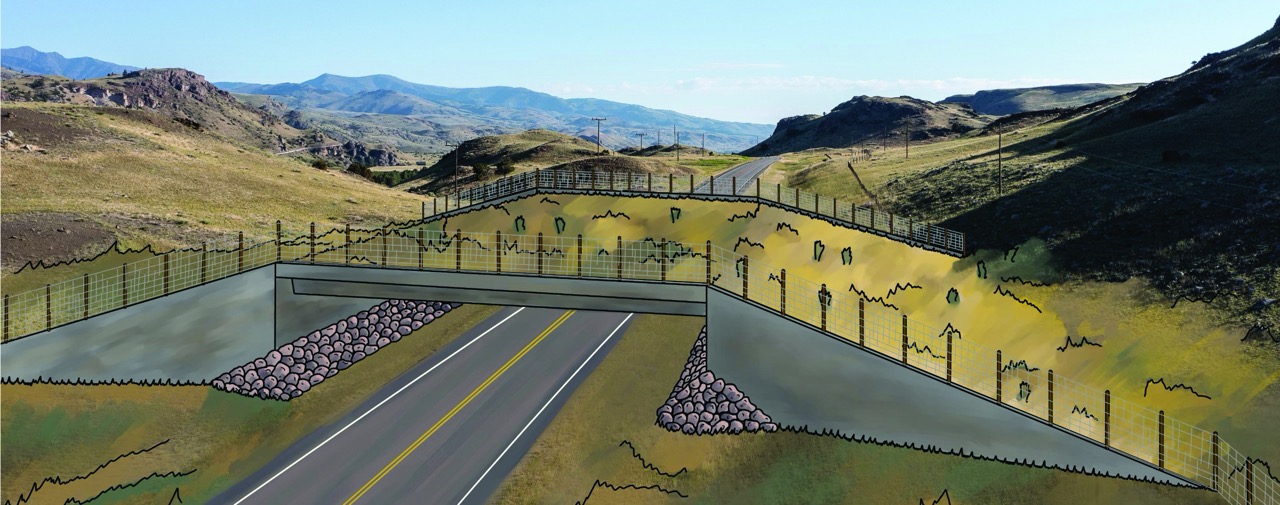

YSP’s first priority is building two wildlife overpasses near Dome Mountain on one of the highway’s most lethal stretches, an expanse of grassland where elk and other ungulates love to roam. Many people refer to driving that section as “running the gauntlet,” and YSP has logged 149 carcasses there, over half of them elk, between 2012 and 2023.

“If you’re there in the winter, there are literally hundreds of elk on both sides of the highway that are bedded down in the winter, and you see them get close to you and you’re like, holding on for dear life going 70,” said London Bernier, a communications associate at the Greater Yellowstone Coalition.

“If you’re there in the winter, there are literally hundreds of elk on both sides of the highway that are bedded down in the winter, and you see them get close to you and you’re like, holding on for dear life going 70,” said London Bernier, a communications associate at the Greater Yellowstone Coalition.

PHOTO BY FISCHER GENAU

Yellowstone Safe Passages chose the Dome Mountain site based on its U.S. 89 Wildlife and Transportation Assessment, which they created with the Center for Large Landscape Conservation and the Western Transportation Institute in 2022. The assessment uses data on traffic statistics, roadkill, and wildlife movement, combined with expert opinions and community input to outline solutions for wildlife-vehicle collisions on Highway 89. In addition to Dome Mountain, the assessment identified six more priority areas where overpasses, underpasses, culverts, bridges, and fencing would improve the safety of travelers and wildlife.

“I think the hope is, with those seven priority areas, to start checking off the biggest ones first, like that herd of elk that lives at Dome Mountain,” Bernier said. “Then over time, the hope is to do projects at each of those locations, so you have a better chance of covering the whole 55 miles.”

In 2024, Yellowstone Safe Passages set things in motion. They applied for and were awarded a grant for a feasibility study to be conducted at the Dome Mountain site, and the study is scheduled to commence later this year. If everything goes to plan, it will take a year-and-a-half to complete. Then, if the overpass is deemed “feasible,” YSP must raise the money to build it. And it won’t be cheap.

Together, the Dome Mountain overpasses come with a price tag of $30-40 million, but Shana Drimal, a wildlife program manager for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, says that wildlife crossings usually end up paying for themselves. Every time someone hits an elk, it costs an average of $17,000 with vehicle expenses, insurance, and potential hospital bills. A wildlife overpass—combined with fencing to funnel animals towards it—has been shown to reduce vehicle-animal collisions on a particular stretch of road by over 90%, and over time, the money saved from each collision prevented adds up.

Other places in the United States have realized the advantages of wildlife crossings, and they’re building more to reap the benefits.

“I think the hope is, with those seven priority areas, to start checking off the biggest ones first, like that herd of elk that lives at Dome Mountain,” Bernier said. “Then over time, the hope is to do projects at each of those locations, so you have a better chance of covering the whole 55 miles.”

In 2024, Yellowstone Safe Passages set things in motion. They applied for and were awarded a grant for a feasibility study to be conducted at the Dome Mountain site, and the study is scheduled to commence later this year. If everything goes to plan, it will take a year-and-a-half to complete. Then, if the overpass is deemed “feasible,” YSP must raise the money to build it. And it won’t be cheap.

Together, the Dome Mountain overpasses come with a price tag of $30-40 million, but Shana Drimal, a wildlife program manager for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, says that wildlife crossings usually end up paying for themselves. Every time someone hits an elk, it costs an average of $17,000 with vehicle expenses, insurance, and potential hospital bills. A wildlife overpass—combined with fencing to funnel animals towards it—has been shown to reduce vehicle-animal collisions on a particular stretch of road by over 90%, and over time, the money saved from each collision prevented adds up.

Other places in the United States have realized the advantages of wildlife crossings, and they’re building more to reap the benefits.

A female elk crossing the road in Yellowstone National Park causing a traffic jam as a tourist takes pictures as they slowly pass. ADOBE STOCK PHOTO

There’s a video on the Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s YouTube channel that shows 47 pronghorn using an overpass built at Trappers’ Point on Highway 191. Pronghorn are the fastest land animals in North America, and in the video, some of them cross the bridge running full bore, gathering speed on the downslope before shooting through a gap in the fence and out onto the grassland.

The Trappers’ Point crossing is the first wildlife overpass built in Wyoming, and it’s one of two 40-foot tall, 150-foot wide concrete arches that were built on a 12-mile stretch of roadway between the Wind River Range and the Bridger-Teton National Forest in 2012. The crossings were designed to reconnect a historic pronghorn migration route, and before their construction, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department calculated that about 140 animals were being struck by vehicles in that stretch each year, amounting to around $500,000 in damages. After the overpasses were built, along with six underpasses and several miles of fencing, wildlife-vehicle collisions in the area dropped by around 80%.

The Trappers’ Point crossing is the first wildlife overpass built in Wyoming, and it’s one of two 40-foot tall, 150-foot wide concrete arches that were built on a 12-mile stretch of roadway between the Wind River Range and the Bridger-Teton National Forest in 2012. The crossings were designed to reconnect a historic pronghorn migration route, and before their construction, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department calculated that about 140 animals were being struck by vehicles in that stretch each year, amounting to around $500,000 in damages. After the overpasses were built, along with six underpasses and several miles of fencing, wildlife-vehicle collisions in the area dropped by around 80%.

“These are proven solutions,” said Angi Bruce, the director of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

“They are pricey. They’re extremely pricey, but there aren’t many things in my job that I can say that we can do and have 100% success, and this is one of those. We don’t have to test it. It’s not trial and error. We know… that they will be successful, and we will save wildlife.”

Wyoming has identified a total of 40 priority sites for wildlife crossings of some kind, and they’re about to break ground on the Kemmerer wildlife crossing project on U.S. 189, which will include five underpasses and one overpass along a 30-mile corridor. Bruce says that wildlife crossings have been a huge success in Wyoming, and the Game and Fish Department and Wyoming Department of Transportation hope to continue building more as long as federal funds remain available.

Everywhere they’re built, from Florida and California to Colorado and New Mexico, wildlife crossings are largely popular and prove to be effective at saving both lives and money in the long term. Already in Paradise Valley, public sentiment is very positive. Anderson has spent hundreds of hours talking to people in the area about wildlife crossings, and he’s learned that, “everyone relates to the issue. They relate to it in different ways, though.”

Anderson said that some of the people he talks to are mostly concerned for the wellbeing of the animals, while others align more with the human safety side of the issue. The third group, which Anderson says is by far the largest, is concerned about the economic impact of wildlife-vehicle collisions. Shana Drimal from GYC has also seen a variety of people in favor of crossings.

“There’s broad support across the spectrum,” Drimal said.

Not everyone in the valley is bought in yet—some locals are wary of change, or don’t trust that the money spent on crossings will be a good investment, while some landowners in Paradise Valley are wary of having one on their own property. But Anderson and Drimal agree that the majority of people there are in favor of wildlife crossings. So why has it taken so long to build one?

“They are pricey. They’re extremely pricey, but there aren’t many things in my job that I can say that we can do and have 100% success, and this is one of those. We don’t have to test it. It’s not trial and error. We know… that they will be successful, and we will save wildlife.”

Wyoming has identified a total of 40 priority sites for wildlife crossings of some kind, and they’re about to break ground on the Kemmerer wildlife crossing project on U.S. 189, which will include five underpasses and one overpass along a 30-mile corridor. Bruce says that wildlife crossings have been a huge success in Wyoming, and the Game and Fish Department and Wyoming Department of Transportation hope to continue building more as long as federal funds remain available.

Everywhere they’re built, from Florida and California to Colorado and New Mexico, wildlife crossings are largely popular and prove to be effective at saving both lives and money in the long term. Already in Paradise Valley, public sentiment is very positive. Anderson has spent hundreds of hours talking to people in the area about wildlife crossings, and he’s learned that, “everyone relates to the issue. They relate to it in different ways, though.”

Anderson said that some of the people he talks to are mostly concerned for the wellbeing of the animals, while others align more with the human safety side of the issue. The third group, which Anderson says is by far the largest, is concerned about the economic impact of wildlife-vehicle collisions. Shana Drimal from GYC has also seen a variety of people in favor of crossings.

“There’s broad support across the spectrum,” Drimal said.

Not everyone in the valley is bought in yet—some locals are wary of change, or don’t trust that the money spent on crossings will be a good investment, while some landowners in Paradise Valley are wary of having one on their own property. But Anderson and Drimal agree that the majority of people there are in favor of wildlife crossings. So why has it taken so long to build one?

A conceptual rendering by Matthew Bell shows one of the proposed wildlife overpasses at Dome Mountain. Yellowstone Safe Passages estimates the two structures will cost $30-40 million. RENDERING COURTESY OF MATTHEW BELL / WILD ENGINEERING GROUP

In Montana, wildlife crossings are hard to pay for. Montana’s tax base is smaller than other states like Colorado that have invested in these structures, and the money that is available, like the funds raised by taxing marijuana that is designated for conservation efforts, is in high demand.

Anderson calls funding the 800-pound gorilla, and he says the big thing missing is a public-private partnership that raises money directly for wildlife crossings. A public-private partnership involves a nonprofit that acts as a kind of purse, receiving large amounts of money from donors and working in partnership with the Montana Department of Transportation and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks to match grants received at the federal level. Anderson says that Yellowstone Safe Passages is very close to establishing this kind of public-private partnership in Montana, and he hopes to start fundraising aggressively in 2026 to pay for the Dome Mountain overpass. His goal is for YSP to raise $30-50 million before Montana’s 2027 legislative session.

But Anderson doesn’t want to stop there: “We could probably spend a billion dollars on wildlife crossings in Montana over the next 20 years, if not more. It just kind of depends on how bad we want it. How much do we want this landscape to be intact for wildlife for many generations down the road, considering the pretty substantial development pressures we’ve experienced in Montana the last 40 years?”

More and more people will keep moving to Paradise Valley, and Anderson says this kind of ex-urban sprawl poses a severe threat to a wild and intact landscape. Right now, traffic volume on Highway 89 is considered medium, which is the perfect recipe for wildlife-vehicle collisions—low enough for wildlife to try to cross but high enough for many of them to get hit. If there’s enough traffic on a road, however, something happens called the barrier effect. Passing cars create a near-impenetrable barrier that isolates animal populations on each side of the road because crossing it becomes so dangerous that they give up entirely.

Anderson calls funding the 800-pound gorilla, and he says the big thing missing is a public-private partnership that raises money directly for wildlife crossings. A public-private partnership involves a nonprofit that acts as a kind of purse, receiving large amounts of money from donors and working in partnership with the Montana Department of Transportation and Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks to match grants received at the federal level. Anderson says that Yellowstone Safe Passages is very close to establishing this kind of public-private partnership in Montana, and he hopes to start fundraising aggressively in 2026 to pay for the Dome Mountain overpass. His goal is for YSP to raise $30-50 million before Montana’s 2027 legislative session.

But Anderson doesn’t want to stop there: “We could probably spend a billion dollars on wildlife crossings in Montana over the next 20 years, if not more. It just kind of depends on how bad we want it. How much do we want this landscape to be intact for wildlife for many generations down the road, considering the pretty substantial development pressures we’ve experienced in Montana the last 40 years?”

More and more people will keep moving to Paradise Valley, and Anderson says this kind of ex-urban sprawl poses a severe threat to a wild and intact landscape. Right now, traffic volume on Highway 89 is considered medium, which is the perfect recipe for wildlife-vehicle collisions—low enough for wildlife to try to cross but high enough for many of them to get hit. If there’s enough traffic on a road, however, something happens called the barrier effect. Passing cars create a near-impenetrable barrier that isolates animal populations on each side of the road because crossing it becomes so dangerous that they give up entirely.

“If we’re not careful, we actually could lose the place,” Anderson says. “That’s part of the reason why I think the vision needs to be big and bold.”

But it takes time to build this kind of infrastructure. People working on wildlife crossings have to think in decades, not months, first building community support and gathering data, then applying for grants, conducting feasibility studies, and raising money before finally actually putting a shovel in the ground. “I’ve had to learn patience and perseverance around much of the conservation work that we’re involved in, but I would say in particular, wildlife crossings take a really, really long time,” Drimal said. “I just had to learn that none of this gets done overnight.”

But it takes time to build this kind of infrastructure. People working on wildlife crossings have to think in decades, not months, first building community support and gathering data, then applying for grants, conducting feasibility studies, and raising money before finally actually putting a shovel in the ground. “I’ve had to learn patience and perseverance around much of the conservation work that we’re involved in, but I would say in particular, wildlife crossings take a really, really long time,” Drimal said. “I just had to learn that none of this gets done overnight.”

Elk crossing road. PHOTO BY MARK GOCKE

If everything goes to plan—and that’s a big if—the Dome Mountain wildlife overpass could be completed by the fall of 2029, and for Anderson, it would be the fulfillment of a nearly lifelong goal.

“To me, to have overpasses and underpasses where wild creatures can cross roadways in a safe way and also keep people safe too—this is deeply spiritual work. This is about our connection to the places that we call home and the places that sustain us…and in theory, ecosystems heal or become more resilient by reconnecting more of the system to itself.”

Once a crossing is built, it won’t take long for animals to start using it. The first to explore the strange, grassy corridor would be mule and whitetail deer, followed closely by pronghorn and Dome Mountain’s elk herds, emboldened by their ungulate cousins’ success. Bison would come soon after, and eventually, even the wary predators like bears and wolves would take their first tentative trips over the crossing. Finally, even the occasional lynx or mountain lion would chance it, following in the footsteps of all the other residents of the valley and passing safely over the dull roar of the traffic below.

For Anderson, an overpass at Dome Mountain would just be the beginning: “I think when that day comes, I’m going to be jumping up and down with joy, and at the same time be like, great, we’ve got more work to do.”

“To me, to have overpasses and underpasses where wild creatures can cross roadways in a safe way and also keep people safe too—this is deeply spiritual work. This is about our connection to the places that we call home and the places that sustain us…and in theory, ecosystems heal or become more resilient by reconnecting more of the system to itself.”

Once a crossing is built, it won’t take long for animals to start using it. The first to explore the strange, grassy corridor would be mule and whitetail deer, followed closely by pronghorn and Dome Mountain’s elk herds, emboldened by their ungulate cousins’ success. Bison would come soon after, and eventually, even the wary predators like bears and wolves would take their first tentative trips over the crossing. Finally, even the occasional lynx or mountain lion would chance it, following in the footsteps of all the other residents of the valley and passing safely over the dull roar of the traffic below.

For Anderson, an overpass at Dome Mountain would just be the beginning: “I think when that day comes, I’m going to be jumping up and down with joy, and at the same time be like, great, we’ve got more work to do.”