By Leath Tonino

If I were to choose one book to keep on the truck’s dashboard beside the binoculars, one book to stuff into the backpack along with GORP and jerky, one book to inspire and inform and enrich my ongoing exploration of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem — what would it be?

Hmm…

Wapiti Wilderness by Margaret and Olaus Murie? Grizzly Years by Doug Peacock? A Climber’s Guide to the Teton Range by Leigh Ortenburger and Renny Jackson? The Yellowstone Story by Aubrey Haines? Journal of a Trapper by Osborne Russell? A Hunger for High Country by Susan Marsh?

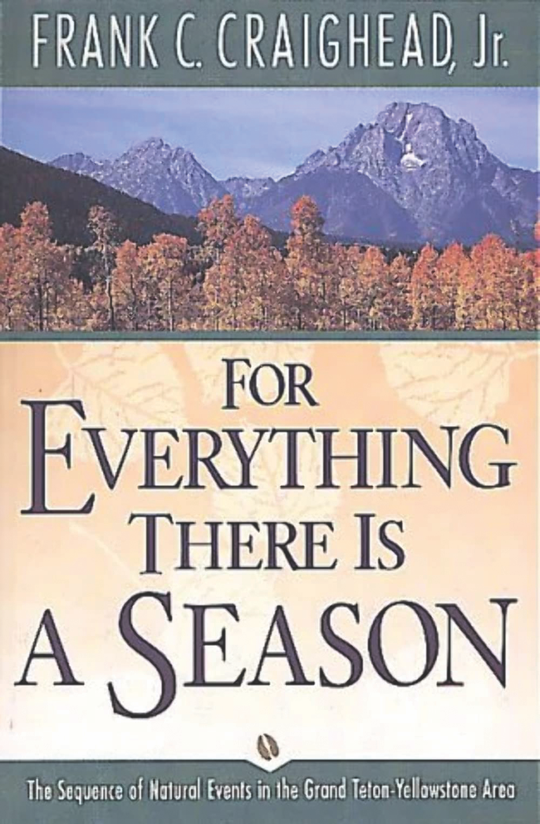

Good options, but no, no, no, no, no, and no. The answer, for me, is a slim paperback published in 1994 (reprinted in 2001), chock full of facts and photos, details and dates, flora and fauna, earth and earth and always more earth. And it’s full of something else, too. Something subtle and elegant and powerful. Something that goes by the less-than-glamorous (and less-than-household) name of phenology.

Phenolowhat?

We’ll get there in a moment.

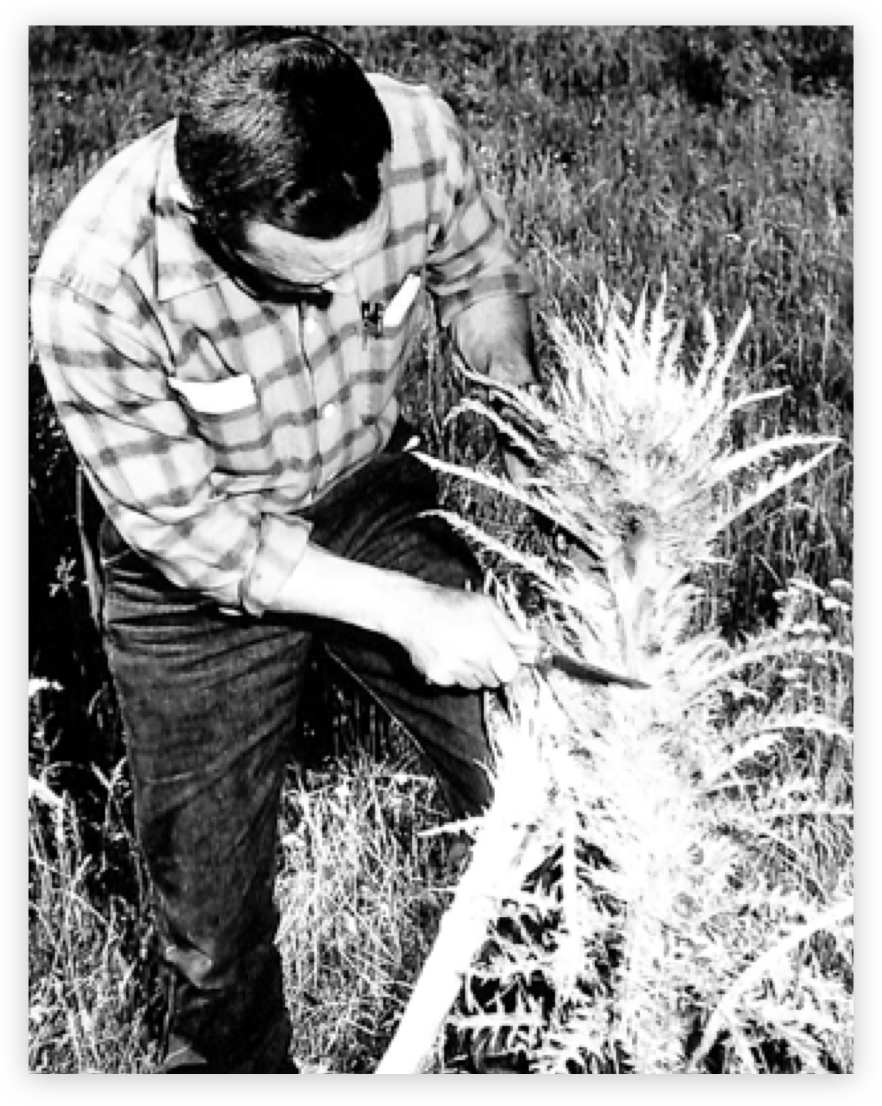

Frank and his identical twin brother John were pioneering wildlife biologists, tireless conservationists, and rugged outdoorsmen who rank with Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, and Ansel Adams in the pantheon of famous twentieth-century nature advocates/experts/lovers. Born in 1916, the bros wrote and photographed for National Geographic (fourteen articles in total), conducted long-term research on Yellowstone’s grizzly population (they were the first to put radio-tracking collars on large animals), petitioned for the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (the bill passed in 1968), and hiked everywhere in the GYE (everywhere).

OImpressive resume, no doubt. But undergirding these efforts and accomplishments was a quieter passion, an inconspicuous pursuit: old-school, down-and-dirty, flannel-and-denim natural history.

Which brings us back to…

Phenology is the study of cyclic and seasonal phenomena. Birds migrating, then establishing territories, then laying eggs. Plants budding, then flowering, then producing seeds, then withering, then returning to the soil. Ice melting from an alpine tarn in June, then reforming in October. As the title of Frank’s book suggests, sequencing these events — locating them in time, in the roundness of the year — is the phenologist’s bailiwick. And basic observation — senses on high alert, few tools and tricks required — is the phenologist’s modus operandi.

It’s a lifestyle: looking, listening, jotting notes. Henry David Thoreau’s magnum opus isn’t Walden, but rather the two-million-word, seven-thousand-page, fourteen-volume journal he kept throughout the 1850s, a sprawling record of arrivals and departures, loopings and layerings, ecological happenings. For Everything There Is A Season grew from a similar practice of sustained attention to the local environment. Luckily, though, Frank’s book is only 208 pages and weighs just over a pound, perfect for on-the-move browsing. Furthermore, it’s organized chronologically, week by week, and is thus very easy to use, very welcoming of the novice naturalist, the would-be phenologist.

Imagine that you’ve walked a trail for three or four miles. Now you’re resting in a meadow fringed by dark pines, cut diagonally by a gurgling creek. Boots off and socks peeled. Sun shining. Okay, flip to page 122 — Sept. 4 to 10 — and in short order you’ll learn…

Spongy white snowberries are maturing. Mountain ash berries are glowing bright orange. Sandhill cranes are flocking and calling, preparing to fly south. Red-tailed hawks have left the nest and are fending for themselves, whereas juvenile Swainson’s hawks are begging their parents for food. Grizzlies are fattening up on voles and bulbs in grass-sagebrush habitats, but you might glimpse one digging its winter den at the foot of a big conifer, usually on a north-facing slope. Ground squirrels have disappeared into their burrows and won’t emerge again for nine months. Bull elk are battling, amassing harems. Mule deer, moose, and pronghorn are likewise rutting. Harebell, geranium, giant hyssop, scarlet gilia, yarrow, lupine, tansy, coneflower, and other species may still be found blooming in favored sites. Deciduous trees and understory bushes, shrubs, and herbs are beginning to show fall colors. Temperatures are dropping, nights stretching as the equinox approaches.

And on and on and on and on.

Earlier, I described Frank’s book as full of earth, full of phenology. This is true, obviously. But here’s the description I really want to offer: It’s also full of crescendos and decrescendos, hidden pianissimo events, bold forte events, interpenetrating arpeggios, complex polyrhythms, stacked harmonies and soaring melodies of place. Music, that’s what I hear. Symphonic in structure and scope. Beautiful beyond words.

IThe point I’m trying to make is that the individual pages of this book are indeed a pleasure, an education, a revelation, yet it’s the complete text, all four dynamic seasons bound between covers, the entire year in your hands, that conveys a feeling — a feeling — of balance and wholeness, of association and synchrony, of flowing pattern and patterned flow.

Ecophilosopher Paul Shepard claimed that phenology leads us to “a deeper understanding and more refined sense of mystery.” Is that a paradox, understanding and mystery side by side, coexisting?

Nah. It’s merely a way of saying phenology — and a certain unique book that lives on the dashboard beside the binos, that regularly rides in the backpack — gets us outdoors, into the world of bison and spruce, warbler and trout, waffling aspen leaves and sparkling frost, a vast and intricate terrain where observation ultimately, inevitably, births curiosity, wonder, and awe.