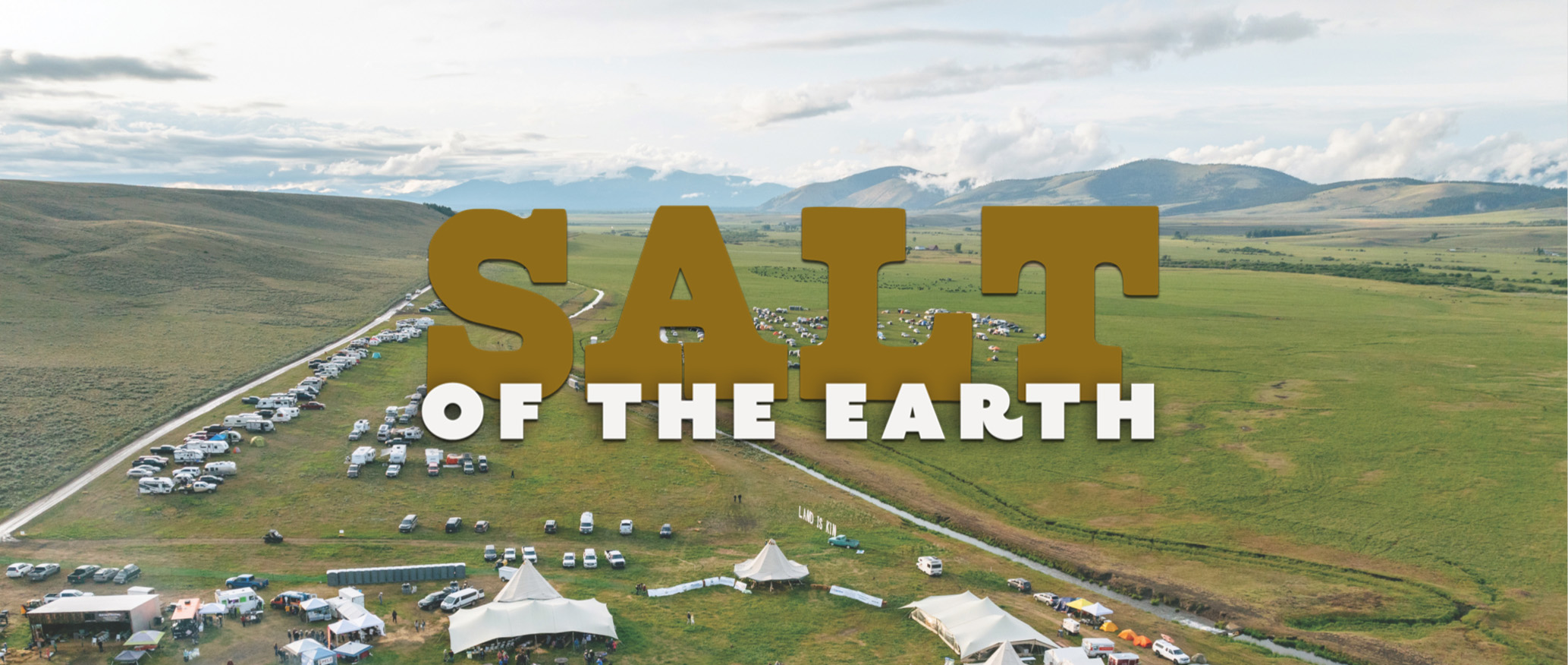

Some came for the music, folksy acts playing to a crowd swaying on the grass. Some came for the lectures, sitting on hay bales to hear panels about creating bird habitat and ranchers’ mental health. Some came for the vibes, browsing stands of handmade beeswax candles and oil paintings of elk. But all 2,800 attendees at the Old Salt Festival came for the meat.

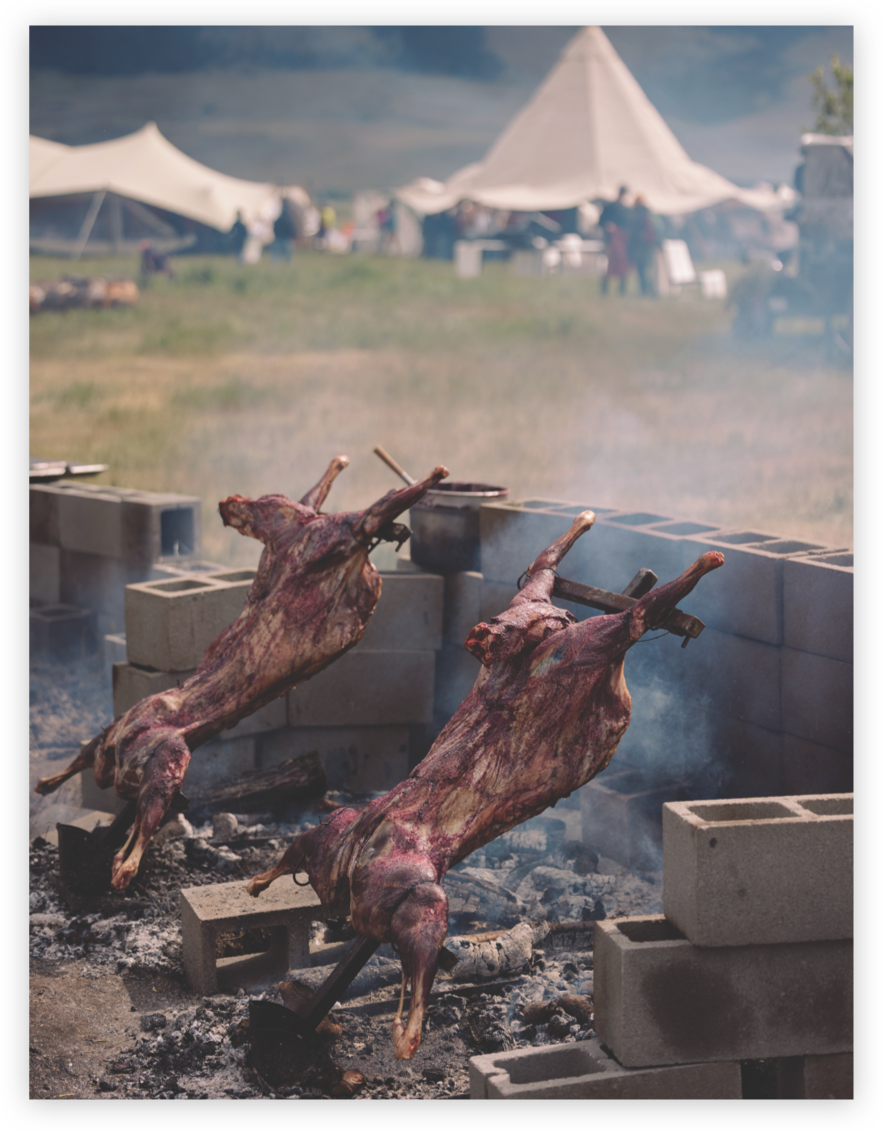

All day, chefs had been tending crackling cookfires in the center of the festival grounds on the Mannix Family Ranch in Helmville, Montana. Carrots, corn, and cabbage from local farms hung suspended over one blaze; a pair of spread-eagled lambs, raised 100 miles to the east, roasted over two others. By midafternoon, the line to taste the samples—with a beef dip sandwich and a lamb-and-veggie bowl, it was really a whole meal’s worth of food—was hundreds deep. Tanned men in cowboy hats and knee-high muck boots stood next to women in pioneer-chic gingham dresses and nose rings. Once served, strangers grouped up around wide standing tables, the jus dribbling down their chins as they grinned their approval to each other.

By Elisabeth Kwak-Hefferan

Montana’s Old Salt Co-op aims to revolutionize the meat business, one grass-fed steak at a time.

An annual event like this—a three-day mix of regenerative agriculture conference, Americana concert, arts fair, and food fest—might seem like an odd addition to a meat company’s portfolio. But for five-year-old Old Salt Co-op, Old Salt Festival is a natural fit. Bringing people together, over fire and meals, to support a regional food system is exactly what the brand is about. More than just fun, the festival is “a cultural gathering for change,” Cole Mannix, Old Salt Co-op’s president and co-founder, said. Mannix and his partner ranchers want nothing less than to change the way meat goes from pasture to plate. And they’ve built an entirely new system to show

the way.

Cole Mannix, 41, grew up on a large cattle ranch in the Blackfoot River Valley, part of the fifth generation of a family that has been on the land since 1882. As a kid, he moved cows on horseback, fixed fences, and made hay. He recalls late-night dinners after ranch work was done with his parents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, swapping stories about family legends (like that time a young Cole drove the tractor off a 15-foot cliff).

Still, getting into the family business wasn’t a foregone conclusion. Mannix studied biology and philosophy in college, then flirted with becoming a priest, before taking a job at the conservation nonprofit Western Landowners Alliance. All the while, he was turning over big ideas about a conventional food system that prizes short-term profit over long-term stewardship and forces ranchers to work on razor-thin margins. “I felt that the commodity system that we have all sold into for generations is an extractive business environment in which we won’t last,” he said, “and that doesn’t serve either people, from the standpoint of nourishment, or land, from the standpoint of ecological health.”

the way.

Cole Mannix, 41, grew up on a large cattle ranch in the Blackfoot River Valley, part of the fifth generation of a family that has been on the land since 1882. As a kid, he moved cows on horseback, fixed fences, and made hay. He recalls late-night dinners after ranch work was done with his parents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, swapping stories about family legends (like that time a young Cole drove the tractor off a 15-foot cliff).

Still, getting into the family business wasn’t a foregone conclusion. Mannix studied biology and philosophy in college, then flirted with becoming a priest, before taking a job at the conservation nonprofit Western Landowners Alliance. All the while, he was turning over big ideas about a conventional food system that prizes short-term profit over long-term stewardship and forces ranchers to work on razor-thin margins. “I felt that the commodity system that we have all sold into for generations is an extractive business environment in which we won’t last,” he said, “and that doesn’t serve either people, from the standpoint of nourishment, or land, from the standpoint of ecological health.”

Mannix’s family had long practiced regenerative ranching, a style that prioritizes soil health, water quality, and biodiversity. But in a market dominated by the rock-bottom prices of giant grocers like Walmart and Costco, “There’s no way to maintain good stewardship at the margins it requires to stay on those shelves,” Mannix said. The conventional meat industry incentivizes Montana ranchers to overgraze their lands and sell their cows to one of a handful of feedlots and meatpacking companies. Mannix imagined a better way. “I thought, well, I can’t change the big system, but I can build a little system that is a model of what I care about,” he said.

In the fall of 2020, he asked a few ranchers with similar values to meet. Some of them, like him, had already tried, and failed, to start their own regenerative meat brands. “We’ve been putting regenerative fuel into a conventional engine,” Mannix said. What they needed was a whole new car.

Over two days (it was supposed to be one, but a snowstorm fortuitously trapped them for an extra day), Mannix and his handpicked collaborators brainstormed what it would take to build a regional meat economy for Montana. “Most of the conversation was visionary,” remembered Hilary Zaranek, a partner in J Bar L Enterprises, which operates four regenerative ranches across the state, and one of Old Salt Co-op’s founding members. “How do we take all of these ethics and values around our relationship with the land and with each other, and make a product and put it in front of a person who also cares about those values?”

In the fall of 2020, he asked a few ranchers with similar values to meet. Some of them, like him, had already tried, and failed, to start their own regenerative meat brands. “We’ve been putting regenerative fuel into a conventional engine,” Mannix said. What they needed was a whole new car.

Over two days (it was supposed to be one, but a snowstorm fortuitously trapped them for an extra day), Mannix and his handpicked collaborators brainstormed what it would take to build a regional meat economy for Montana. “Most of the conversation was visionary,” remembered Hilary Zaranek, a partner in J Bar L Enterprises, which operates four regenerative ranches across the state, and one of Old Salt Co-op’s founding members. “How do we take all of these ethics and values around our relationship with the land and with each other, and make a product and put it in front of a person who also cares about those values?”

That second part was the toughest nut to crack. The crew—Zaranak and her husband, Andrew Anderson, plus Cole’s brother, Logan Mannix, and Cooper Hibbard of Sieben Live Stock Company in Adel, Montana—were already committed to regenerative ranching. “But that only gets you five percent of the way,” Mannix said. “Getting their product to market profitably is an incredible mountain to climb.”

But what if they could create a much smaller system, one in which livestock were raised, slaughtered, distributed, and consumed right there in Montana? One that controlled each step of the process and rewarded producers for their ecological values? It would take a huge upfront investment and plenty of risk. Still, Mannix said, “We decided that the status quo was riskier than anything we might do.”

Around lunchtime in Helena, Montana, diners begin to trickle into a corner building in the lively Last Chance Gulch district. Up front, shoppers browse a butcher’s case of New York strip steak and kielbasa sausage; a sign on the glass explains the difference between grass-finished and grain-finished beef. Behind the wooden tables and framed ranch photos on the walls, a wood-fired grill the size of a St. Bernard flares up to meet a rotating menu of steak specials. Free plant-based diapers are stocked in the bathroom.

But what if they could create a much smaller system, one in which livestock were raised, slaughtered, distributed, and consumed right there in Montana? One that controlled each step of the process and rewarded producers for their ecological values? It would take a huge upfront investment and plenty of risk. Still, Mannix said, “We decided that the status quo was riskier than anything we might do.”

Around lunchtime in Helena, Montana, diners begin to trickle into a corner building in the lively Last Chance Gulch district. Up front, shoppers browse a butcher’s case of New York strip steak and kielbasa sausage; a sign on the glass explains the difference between grass-finished and grain-finished beef. Behind the wooden tables and framed ranch photos on the walls, a wood-fired grill the size of a St. Bernard flares up to meet a rotating menu of steak specials. Free plant-based diapers are stocked in the bathroom.

This is The Union, Old Salt Co-op’s premier restaurant. Opened in 2024, it joined the co-op’s first foray into dining, a smashburger joint called The Outpost that sits inside the bar across the street. The steaks (plus sausages, beef liver, and bone marrow butterburgers) all come from Old Salt ranches, and all are aged and cut at the co-op’s own meatpacking facility. To say the food is good is an understatement—under Culinary Director Andrew Mace, The Union snagged a James Beard Award nomination for Best New Restaurant this year, alongside nominees from places like Seattle, New York, Pittsburgh, and Washington, DC.

The two restaurants exist alongside Old Salt Co-op’s direct-to-consumer meat business. These steaks and chops can’t be found on grocery store shelves. Instead, buyers can opt for a meat subscription, in which a package of various cuts and sausages arrive at their doorstep each month, or even go all in on a 225-pound “beef share bundle.” The co-op also sells one-off orders of items like ground beef, tri tip, and ribs. Now, the brand counts about 750 Montana families as customers; they aspire to serve at least 5,000.

With all its arms—the ranches, meat processing facility, meat sales, and restaurants—Old Salt controls every step of the business, from production to distribution to sales. (The festival serves as a kind of marketing tool, among its other aims.) A vertically integrated structure like this ensures that its ranchers, all joint owners of the company, will benefit at every step. “We’re trying to give ranchers more stake in the food system than they’ve been a part of to date,” Mannix said.

The two restaurants exist alongside Old Salt Co-op’s direct-to-consumer meat business. These steaks and chops can’t be found on grocery store shelves. Instead, buyers can opt for a meat subscription, in which a package of various cuts and sausages arrive at their doorstep each month, or even go all in on a 225-pound “beef share bundle.” The co-op also sells one-off orders of items like ground beef, tri tip, and ribs. Now, the brand counts about 750 Montana families as customers; they aspire to serve at least 5,000.

With all its arms—the ranches, meat processing facility, meat sales, and restaurants—Old Salt controls every step of the business, from production to distribution to sales. (The festival serves as a kind of marketing tool, among its other aims.) A vertically integrated structure like this ensures that its ranchers, all joint owners of the company, will benefit at every step. “We’re trying to give ranchers more stake in the food system than they’ve been a part of to date,” Mannix said.

Two more Montana ranches have signed on since the founding group, for a total of five: LF Ranch in Augusta and Cordova Farm in Power. Mannix doesn’t have a strict set of criteria for his partners, other than that each one hires a third-party company to monitor its ecological health. All four of Old Salt’s cattle ranches have also decided to enroll in Audubon’s Conservation Ranching program, which helps ensure healthy bird habitat on private grasslands. “The more important criteria is the way they see the world and the way they see business,” Mannix said. “I trust that they are world-class people with world-class operations.”

And Old Salt’s structure aims to reward that dedication. “What we’re trying to do with Old Salt is keep more dollars on the ranch, feeding the soil,” Anderson, of J Bar L Enterprises, said. A rancher who grew up on land just north of Yellowstone National Park, he said, “I see how important it is to be ranching in a way that is promoting the health of the ecosystem. I really feel like, if we can create a regional food system that can hold those values, and that can compensate people for those values, then all boats will rise.”

“Having control allows us to carry the value system from start to finish,” Zaranek added. “And that is huge.”

Going into its sixth year in business, Old Salt Co-op shows no signs of slowing down. At press time, the company was in the process of acquiring a United States Department of Agriculture meat processing facility, a move that will open the door to wholesale meat sales and allow Old Salt to process meat for other producers, too. (Before that, the company’s license allowed sales only to the brand’s own restaurants and directly to consumers.) Mannix has his eye on opening more smashburger joints and maybe putting on some micro festivals in the same spirit as Old Salt’s flagship event. Perhaps they’ll also partner up with other local Montana meat brands to fulfill larger accounts, like with local hotels.

All of this potential growth will help the co-op absorb more and more of its ranches’ livestock. Right now, to remain economically viable, all the ranchers must still sell most of their animals into the conventional system. But as Old Salt grows, each ranch has been steadily moving higher percentages into the new business.

“Having control allows us to carry the value system from start to finish,” Zaranek added. “And that is huge.”

Going into its sixth year in business, Old Salt Co-op shows no signs of slowing down. At press time, the company was in the process of acquiring a United States Department of Agriculture meat processing facility, a move that will open the door to wholesale meat sales and allow Old Salt to process meat for other producers, too. (Before that, the company’s license allowed sales only to the brand’s own restaurants and directly to consumers.) Mannix has his eye on opening more smashburger joints and maybe putting on some micro festivals in the same spirit as Old Salt’s flagship event. Perhaps they’ll also partner up with other local Montana meat brands to fulfill larger accounts, like with local hotels.

All of this potential growth will help the co-op absorb more and more of its ranches’ livestock. Right now, to remain economically viable, all the ranchers must still sell most of their animals into the conventional system. But as Old Salt grows, each ranch has been steadily moving higher percentages into the new business.

Beyond its own bottom line, the team behind Old Salt also hopes other ranchers will follow the trail it’s been blazing. “Instead of four big packers, I want to see 4,000 little and medium-size packers,” Mannix said. “Instead of Tyson, with 40 food brands, I want to see 40 food brands that are independent from the big guys. I want to see a richer food culture than Applebee’s and McDonald’s.”

All of that will take winning over consumers accustomed to shopping for the cheapest items and convincing them that “invisible” benefits like healthy soil and water are worth a few extra bucks. “Ultimately, what you feed with your food dollar grows,” Mannix said. “Right now, most of us, with most of our dollars, feed an anonymous food system that is extracting from the soil. It’s going down our rivers and washing into our oceans. It’s extracting from biodiversity. It’s paving beautiful places, and it’s making people pretty damn sick.” Old Salt Co-op offers people a way to opt out. Not only by avoiding a damaging system, but also by supporting one that gives back to the landscape.

Each one of the thousands of people who walk into the Old Salt Festival must first pass seven-foot-tall letters spelling out a message against the backdrop of grassy fields and sloping mountains: LAND IS KIN. The same phrase is carved into a wooden sign hanging from the ceiling at The Union. Land is kin. It forms the spiritual core of the business, and it might as well be tattooed across Cole Mannix’s chest.

The very name of this venture, Old Salt, plays off the idea that a sprinkle of salt can improve the flavors of a dish—just as humans can improve the health of the world around them.

“We’re not just parasites, we can actually enhance things and be part of wealth creation that’s not just about us. Where your neighbor’s health is part of yours. Where the rest of the living world can also exist and thrive.” Mannix paused, smiling. “That’s worth dying for. It’s worth living for.”

And for those who love both Montana landscapes and a good steak, it’s certainly worth thinking a little more carefully about where they buy their meat.

All of that will take winning over consumers accustomed to shopping for the cheapest items and convincing them that “invisible” benefits like healthy soil and water are worth a few extra bucks. “Ultimately, what you feed with your food dollar grows,” Mannix said. “Right now, most of us, with most of our dollars, feed an anonymous food system that is extracting from the soil. It’s going down our rivers and washing into our oceans. It’s extracting from biodiversity. It’s paving beautiful places, and it’s making people pretty damn sick.” Old Salt Co-op offers people a way to opt out. Not only by avoiding a damaging system, but also by supporting one that gives back to the landscape.

Each one of the thousands of people who walk into the Old Salt Festival must first pass seven-foot-tall letters spelling out a message against the backdrop of grassy fields and sloping mountains: LAND IS KIN. The same phrase is carved into a wooden sign hanging from the ceiling at The Union. Land is kin. It forms the spiritual core of the business, and it might as well be tattooed across Cole Mannix’s chest.

The very name of this venture, Old Salt, plays off the idea that a sprinkle of salt can improve the flavors of a dish—just as humans can improve the health of the world around them.

“We’re not just parasites, we can actually enhance things and be part of wealth creation that’s not just about us. Where your neighbor’s health is part of yours. Where the rest of the living world can also exist and thrive.” Mannix paused, smiling. “That’s worth dying for. It’s worth living for.”

And for those who love both Montana landscapes and a good steak, it’s certainly worth thinking a little more carefully about where they buy their meat.